Don’t Lose Control

A review of the AAIB Alauda Airspeeder incident report of February 2021.

This piece first appeared in the April 2021 issue of Drone User Magazine (UK). It is reproduced here now to help new drone users to understand that a number of small issues can add up to an eventual failure. It is worth putting simple mitigations and checks in every time you fly to try to avoid your own incident.

Glossary

This little article touches on areas that you may not be familiar with so let’s get a glossary down.

OSC – Operating Safety Case. The set of documents provided to the CAA to obtain an exemption from the Air Navigation Order.

UAS Sector – The department at the CAA that assesses and approves OSC applications.

AAIB – Air Accident Investigation Board. The CAA department that investigates accidents and serious incidents involving aircraft (including drones).

The usual response

When there is an incident in the drone world there are always those willing to jump in with their theories about what went wrong, who should have done something differently and speculation about the impact on the inevitable impact on the industry. Although speculation is regularly criticised as anticipating the outcome of an investigation, in reality I doubt the Air Accident Investigation Board spend much time trawling the drone Facebook groups looking for clues!

However, when investigations do get published, they can make very interesting reading and provide an insight into the workings of other drone operations and even the CAA itself.

A case in point is an incident involving a very large drone (by your average roof inspection standards) called the ALAUDA Airspeeder.

When an Alauda Airspeeder crashed at an invitation-only event in the Sussex Weald in the Summer of 2019, it didn’t grab many headlines. Somehow the risk of a 95kg uncontrolled aircraft 8000ft up in the Gatwick holding pattern didn’t cause nearly as much dismay as the yet unconfirmed “bogies” just six months earlier at the airport itself.

Even the MD of the company involved on the day when houses had been missed by only 40m was openly joking about the crash.

Speaking at the event, Matt Pearson, founder of Alauda apparently said: “We didn’t promise a soft landing! That’s the thing with early technology, these things happen.”

Perhaps what he should have said is, “That’s the thing with incompetently designed and constructed technology, these things happen”.

Well, the point of the air navigation order, the existence of the CAA and associated checks and balances is that these things should not happen.

The AAIB report into the crash is well worth a read if you are at all interested in the process of getting an unusual aircraft like this into the sky. It will also teach you a great deal more about how not to do it. I’ve seen it said that this should become a well-used case study in all sorts of engineering and safety-related subjects well into the future and I’ve no doubt it will. It provides a fantastic insight into the “Swiss cheese” theory of how accidents happen.

Almost everything was wrong with the aircraft, its command system and the operational processes around it. Unfortunately I don’t have space in this article to cover every aspect so I will work in broad-brush terms. If you want to check the details yourself then the report is publicly available here. Simply google Alauda Airspeeder AAIB report.

So what happened?

In short, Alauda, an Australian company determined to bring flying car racing to the masses, brought a MkII unmanned version of their platform to Goodwood to show it off to an invited audience, which included representatives of UAS Sector. Actually, they brought a couple along, after all as any professional operator knows, one drone is no drones…because something can always go wrong…and it did.

To gain permission to fly the Airspeeder, Alauda needed an exemption (because the platform was >20kg), so they made an application for a temporary lifting of the weight limit on the 9th May 2019.

The application was approved on the 3rd July 2019, coincidentally on the day the company had set up in the UK to carry out its initial test flight. Many operators would be very envious of such a prompt turnaround of an OSC for pretty standard set of reduced clearance exemptions.

With a nice fresh exemption in their sweaty mitts, the company carried out its initial test flight on the Goodwood site. It’s a good job there were no spectators for this flight as it resulted in a “hard landing” which caused damage to the landing gear. The company failed to report this incident (as they are required to under the regulations and their OSC) to the CAA, the Australian CAA, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau or the AAIB. I wonder if they even told their mums?!

Of course, they had a spare platform. Unfortunately they weren’t as well equipped with electronics, so they cannibalised the airframe for its electronics control box.

The crash on day one should have provided a clue that all wasn’t as it seemed in terms of quality. Check out the report for details but essentially, if you gave a cage of chimps a soldering iron and random box of components it is possible that they would do a better job of putting the power and control systems together. Not good.

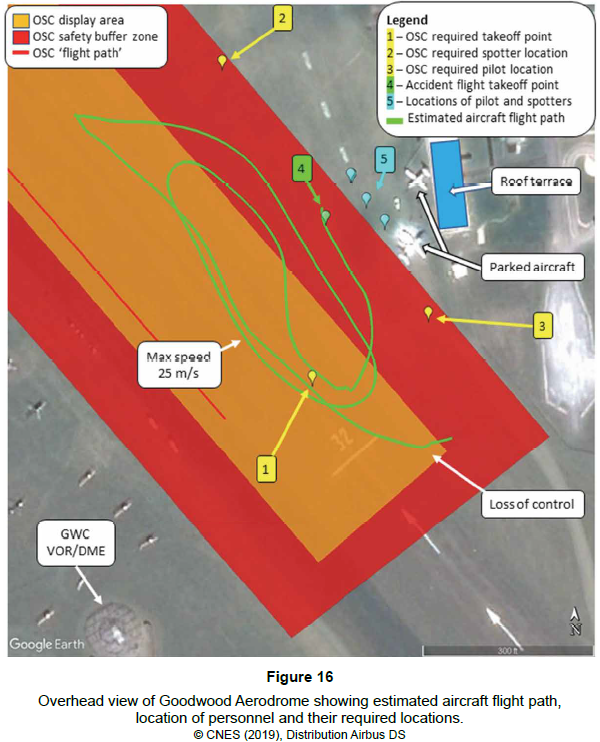

The next day, having crashed the day before, the team set themselves up near the runway. That’s important by the way…because the Airspeeder should have been on the runway. You see, within the operational instructions, the area was split into a flight zone and a safety buffer zone. The aircraft should not have been allowed to stray into the buffer zone without a spotter alerting the pilot to a perimeter breach. However, the pilot decided that the best take-off location was from within the buffer zone. It would be like a standard operator carefully setting up a 30m cordon around his take-off area, then stepping outside it next to a group of onlookers to take off! Bear in mind that all of this was taking place in front of the people who had assessed and signed-off the approval.

Alauder Actual Flight Path

Is it cynical to think that the directors, keen to impress potential investors, decided that safety could take a back seat to an impressive and exciting take-off, closer to the crowd?

The precise location of the remote pilot and spotters is important here. The aircraft was not fitted with any GPS so its position had to be derived externally by the spotters. It can be seen from the flight path (calculated after the event by the AAIB using onboard camera data), that the Airspeeder, having started in the safety buffer zone, preceded to cross back into it for almost a whole run with no attempt to pause and come back into the orange section.

It’s worth noting a couple of other operational failures at this point:

The Airspeeder was being controlled by a transmitter set to 915MHz at 10mW. It was capable of 25mW at 868MHz, the maximum allowed in the UK.

The operator had chosen a frequency which is illegal for airborne use in the UK without the permission of Ofcom – which hadn’t been sought. He could have selected the 868MHz frequency with the higher power output.

An additional transmitter was available to provide redundancy to be used by one of the spotters in an emergency…but it had been left in the workshop.

The pre-flight radio signal strength test took place with the receiver outside the carbon-fibre shell of the Airspeeder. Carbon fibre will happily block or severely attenuate a radio signal. Yes, the antenna for the receiver was located inside the body of the Airspeeder. They hadn’t thought to bring it through the body so that there was a clear external signal path to it.

The pre-flight signal strength test did not include the kill switch functionality.

All spotters were to be equipped with kill switches but in the event only one was available…with the spotter next to the remote pilot. This may not have made much of a difference given that the spotters all seemed to want to stand close enough together to almost hold hands!

Finally, the design of the failsafe in the event of signal loss was a strange one. The DJI, Yuneec, Parrot etc. units we are familiar with will, in the event of signal loss, use GPS to return to their home point. This is such a key requirement that it is included as a condition of an Operational Authorisation to operate in the Specific Category.

“…the small unmanned aircraft shall not be flown:

Unless it is equipped with a mechanism that will cause the small unmanned aircraft to land in the event of disruption to or a failure of any of its control systems, including the radio link, and the remote pilot has ensured that such mechanism is in working order before the aircraft commences its flight”

As the AIrspeeder had no GPS, it couldn’t return to home in the event of signal loss, but it could have been designed to automatically operate the kill switch. It was (theoretically) being demonstrated in a sterile area and the speeds it should have been flown at would have ensured it would come down away from people. But no. Alauda, in their infinite wisdom, had decided that if the control signal were to be lost, then the best thing would be to give the pilot a chance to regain it. Meanwhile, the aircraft was programmed to continue with its last known command.

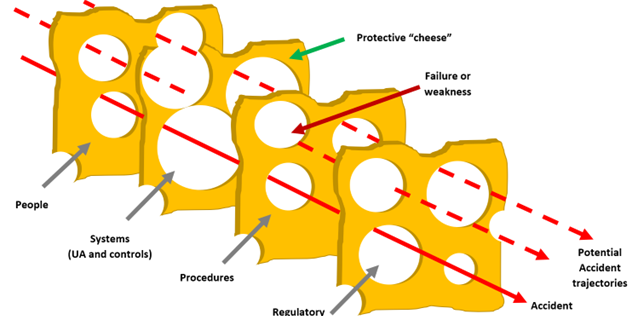

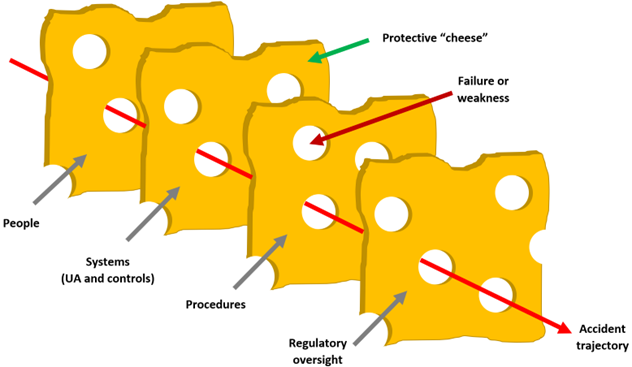

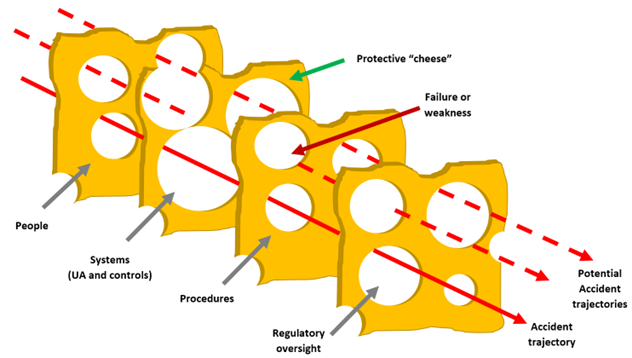

Looking at the above you could be forgiven for thinking that absolutely everything that could go wrong was set up to do just that. There is a safety model called the Swiss Cheese Model. It pictures each element in a safety system as a slice of Swiss cheeseTake me higher…with the traditional holes in it. Provided the holes don’t align all the way through (because one of the elements ensures it is “blocked”) then a safe operation can occur.

Where the holes do align, then everything is set up for an accident, as they were in this case:

Usual Swiss Cheese Model

In this instance there were so many holes through the cheese slices and they were so large that there were a number of potential accident trajectories, some of which could have been a lot worse than the one that occurred. For instance, there were fuel bowsers parked within the safety buffer that the craft was flying in. The crash location was 40m from houses…not on top of them. There was also a large open-air event taking place in the property adjacent to the site. The people there wouldn’t have had the same warning to clear the area that the attendees to the demonstration flight had so wouldn’t have had the opportunity to take shelter.

Probable Swiss cheese model

The ill fated flight

The demonstration flight commenced, and the pilot took a couple of runs up and down the defined strip. Then he lost connection, almost certainly because he was using a frequency close to other users at the site, he had chosen the lowest power option on his transmitter and the design effectively shielded the antenna.

The kill switch (for which a signal test hadn’t taken place) failed to work and the spotters didn’t have access either to their own kill switches or the spare transmitter.

The failsafe kicked in and the Alauda did what was expected of it. It continued with the last control settings it had received.

Take me higher…!

While the gathered guests were quickly shepherded into a building, the Airspeeder continued up, up and away. After the accident, the onboard cameras (which, strictly speaking should never have been there, having not been mentioned in the OSC) came into their own. The AAIB sent the footage to a specialist unit who managed to recreate the estimated flight path and altitude of the Airspeeder. Amazingly it topped out at around 8000ft, well into the airspace used by Gatwick ATC to put airliners into a holding pattern.

What goes up…

…must come down. When it did, the drone hit the ground with an estimated impact force of 28400 Joules. To put that number into perspective, UA’s able to impart 80 Joules of kinetic energy are not allowed to be operated intentionally over people in the Open Category. The impact from this machine was over 250 times greater. The thought of a drone of that size and weight landing anywhere with a population should make your blood run cold…it does mine.

The outcome

What happened to the main players in this incident? After all, the CAA is keen to point out to operators, commercial and hobby, that article 241 of the Air Navigation Order applies to drone users. Article 41 is a catch-all which states that a person must not recklessly or negligently cause or permit an aircraft to endanger any person or property. When the mass of a drone increases, the risk associated with it also rise. This is why there is such a large range of weight classes within the new Open category and why there is a limit of 25kg for a standard Opeartional Authorisation. The theory is that more care has to be taken when considering the conditions under which a platform such as the Airspeeder is allowed to operate.

Of the fifteen safety recommendations in the report, thirteen are directed at the CAA, one at EASA and one at the operator themselves…though it is a very broad recommendation.

I mentioned the possibility of an impact on the industry…and there has been one already.

The CAA department tasked with approving OSC-based authorisations has come under new management since this incident took place. It is also clear that a far more rigorous approach is being taken to OSC applications and renewals. As an adviser to organisations seeking advanced permissions, it is actually heart-warming to see the additional care being taken when reviewing applications. A higher level of justification is being demanded together with stronger evidence of the ability to comply with proposed mitigations. It is likely that obviously templated OSC applications will receive much more scrutiny. This incident has proven that not only does documentation have to be a correct reflection of achievable operational processes but that those involved in the processes have to understand and comply with them fully.

Alauda themselves have generated 53 improvement recommendations and apparently are working through these as part of its plans to continue development of the platform. They have dropped the MkII design and have apparently recruited additional, experienced staff. We can only hope that if they decide to re-visit the UK that the controls on their activities are far more stringent.