CAA Scheme… or scheming?

The background to this piece is simple.

The UK CAA, in its recent Consultation on the 2025/26 Scheme of Charges, dropped the bombshell that there will be a rise of at least 113% in the cost of a PDRA Operational Authorisation application or renewal. The price is slated to rise from £234 to at least £500. I stress at least here because a note in the consultation does allow for a 5.9% increase at the time of implementation to allow for inflation at 1.6% and 4.3% to fund specific activities described elsewhere in the report.

The problem is that nobody actually involved in the industry can see the justification for such rises at what is effectively the lowest rung of Specific Category operations.

The issue was covered by a couple of Geesvana YouTube shows during the week of the consultation launch which can be found here:

How Much? CAA HIKES Drone Fees: Speak Up BEFORE It’s Too Late!

We Found It! BAD Data, BAD Decisions: Can we TRUST the CAA?

The nub of the problem is that when Sean Hickey of Geeksvana requested an explanation from the CAA of the basis of the price increase, he was pointed to the “Efficiency Report” on pages 51 to 59 of the CAA’s Annual Report and Accounts 2023/24 and this is when things started to get interesting.

This is because the first of these pages covers in detail the new Digitising Specific Category Operations (DiSCO) project.

The section provides a figure of “7000 per annum” for the demand today as well as a forecast of “75,000 per annum” looking forward to 2030.

Units of measure please

As we question on the second show, there is no clear statement as to what the unit of measure for the 7,000 or 75,000 figures. They could be packets of HobNobs, furlongs per fortnight or, far more likely, operational authorisations. I would argue that it can only be the third of these given that the whole context of the report section is about the introduction of a system designed to increase the efficiency of the operational authorisation application process.

To be completely fair, I have reproduced the section in full below. See if you can make the numbers 7000 and 75,000 fit anything other than numbers of operational authorisations:

Digitising Specific Category Operations (DiSCO): The DiSCO project is a crucial initiative to enable scalable Beyond-Visual-Line-of-Sight (BVLOS) Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) operations in the UK, transforming the operational authorisation process for RPAS in the Specific category. The project has delivered a standardised approach to risk assessments in this category, along with a new online application tool bringing significant customer benefits and CAA efficiencies. The application process is much easier and quicker, and turnaround time for authorisations has been reduced from weeks to hours. The more consistent and standardised way to assess operational risk, aligned to global standards, enables an efficient application process that is scalable to meet the forecast demand in the industry in the future, from around 7,000 per annum today to over 75,000 per annum by 2030.

Let’s be perfectly clear. This section within this document has been signposted by the CAA communications team by way of explanation as to why the cost of Operational Authorisations have to more than double next year.

The problem is that I will prove to you that the “today” figure of 7000 Operational Authorisation holders is horrendously inaccurate. For that we have to look at the recent timeline of figures provided by the CAA in various contexts. You see, there is a habit of the RPAS team to inflate the figure for some purposes (for instance this Annual Report), whilst providing corrections when pressed. There is an exception in the timeline where the team came up with a fever-dream number for 706 in their safety report covering 2023. The timeline is shown in the second video above, but it bears repeating here.

CAA claimed numbers of Operational Authorisation holders. Source: Various CAA responses and reports via Geeksvana

As a bit of a guide, I have placed green ticks against the figures in which I have confidence and crosses against the “fever-dream” numbers. The confidence comes from the sources, which are either the CAA comms team, which goes through checking process before releasing such data, or the number has come as a result of a formal correction to a report and again has therefore been checked.

This timeline alone should be enough to point to a complete lack of competence in the area responsible for the inaccurate numbers, or worse, the building of a narrative in or to…I don’t know. But there must be a reason that the RPAS team seems to want to exaggerate the size of the work it’s doing.

But I’m afraid it gets worse.

The central figure above is the 7000, which comes from the Annual Report and Accounts under discussion here. Not only is the number misaligned with the 2947 figure released in the corrected safety report in the same month, but it is misaligned with the number given in the same Annual Report that quotes the 7000 figure.

As stated before, the 7000 figure appears on page 59 of the Annual Report and Accounts. The problem is that on page 12 of the same document you will find this within an infographic showing all activities of the CAA.

CAA Accurate number of Operational Authorisation holders. Source: CAA 2023/24 Annual Report and Accounts

Beware, returns may go down as well as up.

Well, would you look at that. Not only is the number nothing like7000, but it also shows a clear reduction in the number of OA-holders from 3620 to 2806. That’s a reduction of over 22% in less than 12 months. What a great growth record!

The CAA appears to have driven through a system that is scalable to cope with an unrealistic number of UAS Operators as of today. A number (7000) that appears to have been made up. I hope to show with one number how unrealistic the top line number of 75,000 is in terms of the number of Operational Authorisation holders by the end of this decade.

The argument is one of logic so please stick with me.

DiSCO is designed primarily to ease applications around Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations in the UK. I have worked in the industry for over 7 years, and have a history of supporting higher-end operators working Operating Safety Case applications. These operators tend to employ multiple remote pilots. This is where the CAA see “Future Flight”. It is aimed at BVLOS operators who will tend to be larger than the sort of operators who are currently limited to Visual Line of Sight only.

However, even with expansion, the number of 75,000 appears highly dubious when you place it in the context of the rest of aviation. Manned aviation is incredibly well developed. It fulfils many niche requirements, some of which will be overtaken by UAS operators in the future. It is also a large sector and those flying include non-commercial, private pilots as well as commercial flyers. Think of these as the hobbyists of manned aviation.

It may therefore surprise you that the number of UK pilots sits at 48,602. That’s right, there are 35% fewer manned pilots today, in a mature industry, than the CAA predicts for the number of organisations that will be employing remote pilots by the end of the decade.

CAA Pilot Licence Holders. Source: CAA 2023/24 Annual Report and Accounts

Let’s make up some numbers

If the CAA can make up figures then so can Eyeup Aerial Solutions. I’m going to do it now. I think a conservative figure would be for an average future flight UAS Operator to employ 5 remote pilots, which are the effective equivalent of manned pilots in an organisation. If we plug those numbers into the CAA’s 75,000 organisations, it looks as though they expect there to be a demand of 375,000 remote pilots. Let’s hope they aren’t relying on the current crop of manned pilots (48,602) to fulfil these BVLOS flying roles….’cos they’re gonna run out pretty quickly!

I can’t help thinking that the numbers being quoted by the CAA, which form the basis of their system, which in turn forms the basis of the 2025/26 price rise, are wholly unrealistic.

1.9292776

There must be a deep, meaningful plan on a spreadsheet showing the expected number of OAs per annum the sector is likely to demand. There must be, otherwise nobody would be foolish enough to le the department spend huge amounts of money preparing for the growth.

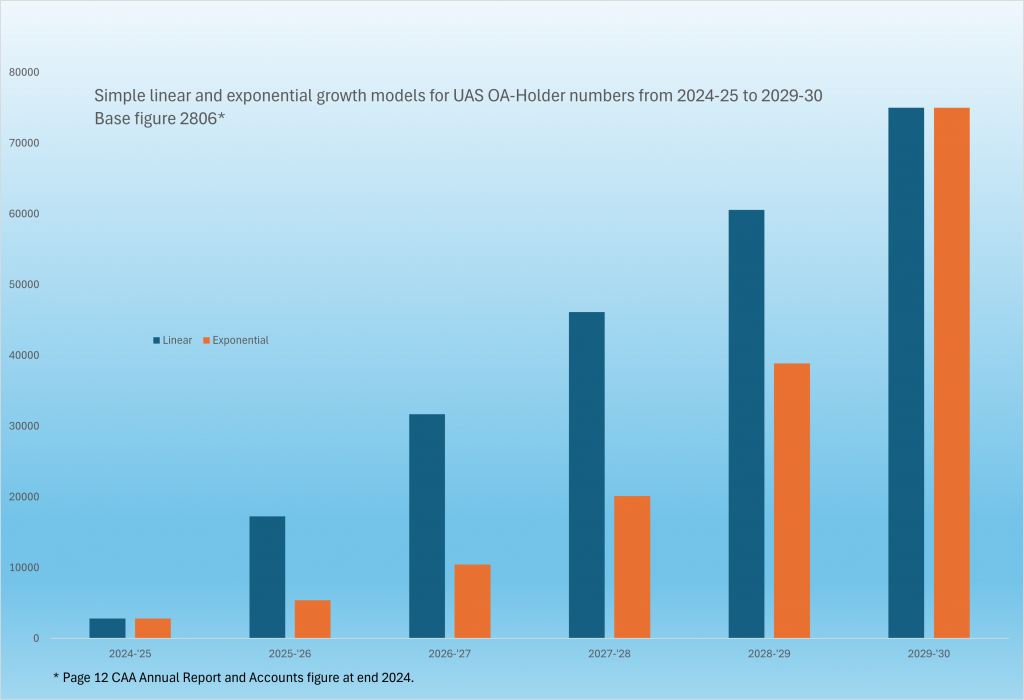

I have no magical view into the machinations of the RPAS department….but I do have Excel on my laptop. So I quickly worked up two models to take us to the current “real” number of OA’s to the mythical 75,000. Both are reasonable in terms of modelling income. The first is a simple linear growth and the second simple exponential model (remember those from the Covid pandemic?) using an annual multiplier of 1.9292776.

The value of these models is that they let us create annual targets to see if the RPAS department is getting anywhere near its targets. There is a caveat to this though….they are not allowed to just make up numbers to present to the board.

Let’s take a look at the growth patters for the number of OAs.

OA-Holder no. growth models 2024 to 2030

Money, money, money.

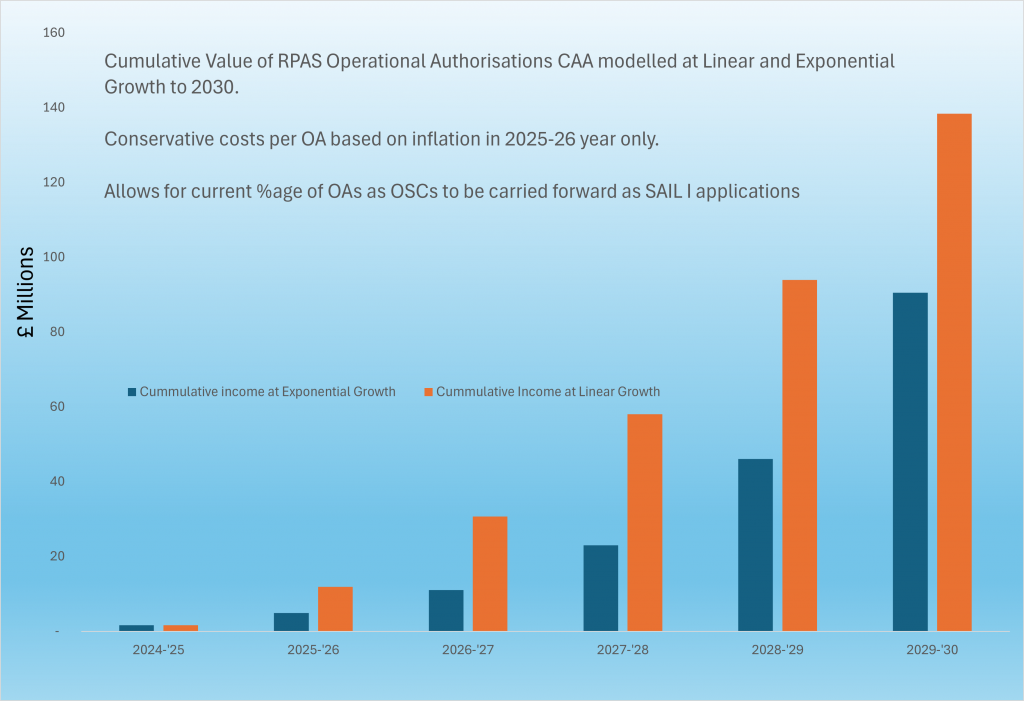

What do the numbers above translate into in terms of income to the RPAS department? This is critical as it gives an idea of whether or not the current cost of the systems being introduced (the investment if you like) is significant or not in terms of the income it will derive. Obviously there are other costs too, such as staffing, but enhanced, more efficient systems should really be reducing the relative costs of these over time.

It’s also worth looking at the projected income averaged over the 6 years involved, since again, these provide a nice comparison against what we are being told is needed today to pay for all these new systems.

Although it is stated on the graph, it’s worth repeating that these are very conservative estimates of income. I have modelled the numbers based on the current percentage of OSCs. This is reasonable since the CAA will be forcing more operators down the OSC route soon if they wish to operate larger UAs in congested areas. However, I have only looked at the most basic “SAIL I” level of OSC equivalent. There will presumably be large amounts of additional income driven by more complex operations in the SAIL II to SAIL VI categories.

I have also ignored inflation and additional CAA annual increases beyond 2025/26, where we know it is is slated at 5.9%. That’s right. Your OA renewal won’t be £500 next year…it is projected to be £530.

Estimated Cumulative Value of OAs to 2030

To save you grabbing your calculator, the average income each year works out at over £15million on the exponential model and more that £23million on the linear model.

If these numbers are anything like the CAA has in its forecasts, then why is it making the low-end VLOS industry pay up front for a system that provides it with no tangible benefits?

It concerns me that the RPAS department can continually provide inaccurate and (deliberately?) misleading data for use in statutory reports and get away with it.

It concerns me that the accountants in the CAA appear to allow these numbers to be used to justify multi-million pound “investments” in poorly scoped systems.

But most of all it concerns me that the CAA thinks it is right that the current crop of small operators, who have blazed the trail in terms of UAS usage, are expected to pay the price for systems set up to benefit much larger operators.

The Scheme of Charges Consultation makes great play of the “user-pays” principle. Well CAA, I’m afraid that PDRA OA-holders didn’t agree to pay for a system designed to benefit other, deeper-pocketed big-industry players.

When you respond to the Scheme of Charges consultation, feel free to link to this blog and the Geeksvana videos as a part of your response.