CAA Hot Weather Warning

There are currently warnings of temperatures rising into the 40’s (Centigrade) in the UK during the coming week. As ever, the UK is poorly prepared for such thermal extremes so various authorities are releasing warnings about reducing travel, avoiding swimming in cold water and staying in the shade. Not wanting to miss out, on the 15th July the UK CAA released its own heat warning to drone users.

Some operators have shrugged their shoulders and put this down to a collective “hysteria” and jumping on the bandwagon. What is the reality in terms of risk to your drone (and you) when flying in such high temperatures?

What is the hazard?

In risk assessment terms, the hazard we are talking about here is overheating. Your UAS is designed and tested to a design specification using components that are working together in close proximity and which generate their own thermal load. The manufacturer understands that it is probably going to be flying for most of the time it is switched on. As well as the active electronics, there are also various mechanical aspects to drone construction that could be adversely impacted by heat. For example, I was surprised at just how many self-adhesive pads were used to help hold my Inspire 1 together when I finally retired it and ripped it apart.

DJI Mini 2 Operating Temperature Range

DJI Matrice 30 Operating Temperature Range

So, we have a bunch of components held together in an enclosed space, some of which are busy generating their own heat. If we’re lucky we also have a fan drawing some of that heat off. The problem comes when the “cool” air being drawn in to reduce the temperature of the electronics is not cool enough to do that. This is where the ambient air temperature comes in.

If a set of electronics has been designed to operate at a temperature and the ambient temperature is above that, there is no guarantee that the electronics will be able to cool themselves. The fan, or external air movement from the props or flight will have been factored into this calculated operating temperature.

As with wind chill in the winter, there appears to be a belief that flowing air is cooler than still air and will help to cool the electronics. The bad news is that wind chill is a physiological effect, not one that is “experienced” by your electronics. If the ambient air hitting the electronics is sitting at 40 degrees C then that is the temperature that the electronics will be impacted by, no matter what the speed of that air. Air at 40C will not be cool enough to draw sufficient heat away from the electronics quickly enough to keep the temperature down. This is why the manufacturer has an upper temperature specification that may be lower than the specification of the individual components used in the design.

Solar Gain

Whether the UA is flying or sitting on the ground waiting to take off, we need to consider the impact of solar gain. The manufacturer of your drone provides you with an operating temperature, which implies flying. Sitting on the ground in the sunshine is not flying and provides an opportunity for a bit of thermal runaway through solar gain…that is the sun hitting your drone.

Most drones these days are not white (like the old DJI Phantoms). Non-white drones will heat up through solar gain as soon as they are out of the shade. This covers most flight scenarios.

Bear with me while I make a quick detour into the concept of solar gain and the real impact it can have on temperatures of anything in the open during warm, sunny periods.

Nice box Mr Stevenson

Thomas Stevenson was a Scottish engineer who was a bit keen on lighthouses. However, he also came up with a cheeky little box that is used to help standardise the environment for taking weather measurements. His design has been refined over the years but essentially does the same job of removing the effects of solar gain (sunshine) on instruments such as thermometers which can have a dramatic impact the reading they give.

Here is a modern version of a Stevenson screen as used by Metcheck. You will see that, as with all versions of the screen down the years, it is painted white as this colour is the best at reflecting the maximum amount of heat.

Stevenson Screen

Because of this standardisation, the temperatures given in weather forecasts are always shade temperatures. As ever, we like a bit of evidence so, unscientific as it may be, I’m hoping this should suffice for anybody who doesn’t think Trump’s idea of drinking bleach to cure Covid was great.

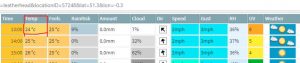

The first is the forecast from Metcheck for today. This site always provides a pretty accurate forecast for my area and is showing a shade temperature of 24C..

Metcheck forecast, Leatherhead, 16th July 2022

This little thermometer lives outside in a shaded place in our garden. We found it when we moved into our house and it is clearly from the 50s or 60s when we still made such things in “England”. It isn’t calibrated but it clearly shows a shade temperature in line with the forecast shade temperature.

Now let’s take a look at the same thermometer after I had left it in today’s sunshine for ten minutes or so.

The reading of 42C is clearly much higher than the shade temperature.

Your components are sitting in their own version of a Stevenson screen. The problem is that, unlike weather instruments, your drone is producing its own heat and the screen isn’t designed for meteorological purposes. It may well be a darker colour than white, which will reduce its ability to shed that heat to the surrounding ambient temperature.

With a shade temperature of 23C, the solar gain is an additional 19C, taking us to around 42deg. Imagine what those numbers are going to be next week if the shade temperatures rise to close to 40C. If you are going to venture out, make sure you don’t keep the drone sat around anywhere that it can heat up more than necessary. Leaving it on the parcel shelf of your car is a definite no-no in these conditions.

At this point you need to be confident that your drone, which you have probably never flown in such high temperatures, can maintain flight and, with various electronic systems inside, remain stable.

By the way, the solar gain will not be “cooled” by flying through the 40-degree air as wind chill effects are purely physiological effects, felt by humans and animals, not a physical one experienced by inanimate objects.

Batteries

Let’s talk about batteries. These little beauties have a lot of responsibility and the chemical reactions that provide the energy also generate a lot of heat. Depending on the drone design, a lot of this heat will be very close to the electronics, which are already struggling to fight against high ambient temperatures and solar gain. If you are going to fly, I can only advise that you keep the drone slow and steady to reduce the heat build up in the first place.

Human Factors

Most aviation incidents (of all types) end up with a human factor as the root cause. Hot weather, the like of which we really aren’t used to in the UK, is a huge risk factor.

Dehydration and the effects of sunstroke are very real risks and will impact an operator without them even knowing. If you are with a flyer, look out for signs of confusion, failure to react to questions/statements, bright red, hot head, headaches, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting and light fever are also possible. Mitigation can be through wearing a hat and ensuring the skin has a light covering but to be honest, in the temperatures expected, the best mitigation is to stay out of the heat.

Mitigations

All is not lost. You can fly on hotter days and remain legal. Remember that you need to remain within the manufacturer’s environmental limitations of your drone and if you are flying under an operational authorisation you need to take the crew health aspects of your Operations Manual seriously.

Sensible mitigations may include:

- Flying during the cooler parts of the day. This will tend to be the earlier hours but the evening may cool down sufficiently too. Just avoid the hottest parts of the day.

- Using an appropriate platform. Most DJI and Autel products are limited to an upper temperature of 40C. But the higher end industrial models such as the Matrice M30 and M300 are rated to 50C.

- Finding shade and staying in it. Keep equipment in the shade. You could use a cool box to keep batteries cool until use but keep an eye out for condensation when they are removed from storage.

- Doubling down on your other mitigations. Really avoid overflight and/or hovering over people. Keep the drone over open ground or strong structures.

- Re-scheduling the flight. Is it really worth flying a job with an increased risk of equipment failure. Coupled with the ability of your insurer to look at weather data and your flight data, it could be the worst business decision of your life.

More info…

If you’re addicted to moving pictures, well done for getting to the end. You may also want to pop across to Firefly UAV’s YouTube channel, where Colin Fyfield gives a few top tips for mitigation in extreme high temperatures.